Everyone has heard of autoimmune diseases, right? About 8% of the U.S. population has an autoimmune disease, and the prevalence is only growing. We’ve all seen a million TV commercials for drugs to treat psoriasis or Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis. You probably know someone who has Type 1 diabetes or celiac disease.

But have you heard of pemphigus vulgaris? It’s a gross sounding name for an extremely rare and terrible condition. Even seasoned medical professionals are rarely aware of it.

It’s also my diagnosis – it’s what makes me weird!

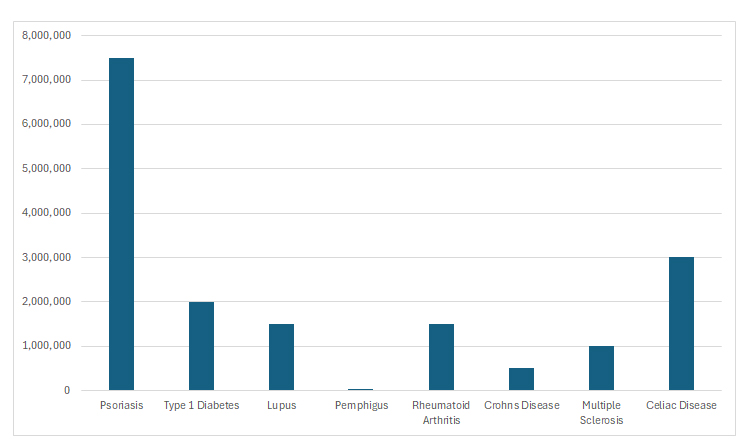

I put this little chart together that shows just how rare pemphigus is compared to some of the more common autoimmune diseases that most people have heard of.

The rareness of this disease means there are fewer studies, less funding, less expertise, and almost no awareness. It’s the reason the average patient takes somewhere between 5 and 10 doctors and ten months to get to an accurate diagnosis.

As I’ve slowly shared my diagnosis with family and friends, everyone is asking what having this disease means for me.

There are detailed medical overviews and an international foundation for patient support, but this is my non-medical description of my illness.

How Pemphigus Impacts Me

Having pemphigus means that my body is attacking itself and destroying the ‘glue’ that holds my skin together. Many people with pemphigus have widespread blistering on their external skin (I have not, personally).

Most people with pemphigus also have extensive, painful mucosal blistering. This has been my particular battle.

The mucosal blistering usually starts in the mouth. From the beginning, I experienced widespread blistering, splitting and sloughing of skin inside my cheeks, on the surface of my tongue, on my gums, on the floor/roof of my mouth, and all the way down my esophagus. The sores don’t heal – they just bleed and become larger and more painful, making it impossible to eat most foods. I lost 30 pounds in just a few months. For much of the past year and a half, I have been unable to eat solid foods. I’ve had brief reprieves when I’ve been on high doses of prednisone, but symptoms quickly return when the steroid doses go down.

The pain is relentless and is not responsive to Tylenol or ibuprofen.

Many patients will also have mucosal ulcers beyond their oral cavity. Our bodies have mucosal tissue everywhere! This means that these painful sores often also appear in a person’s nasal passages, gastrointestinal tract, and genitals. The disease is brutal, disfiguring, and dehumanizing. It impacts a person’s ability to use the bathroom and have sex. A person with this illness is robbed of many basic bodily functions that normal people take for granted. In addition to the physical suffering, the mental and emotional toll is immense.

How Did I Get Pemphigus?

It started somewhere in my DNA. Evidently, I was born with a gene that made me vulnerable to autoimmune diseases in general. Lots of people in my family have autoimmune issues, so this gene really isn’t a surprise.

Pemphigus is not an inherited disease in the way cystic fibrosis or sickle cell anemia are. The gene itself does not pass pemphigus along. In fact, pemphigus rarely happens more than once in a family. The genetic vulnerability is vague – any number of autoimmune diseases might be triggered. Pemphigus is just the disease that chose me.

Pemphigus is a B-Cell mediated disease. That means – when the switch flipped in my body, something went wrong with a few of the B cells being produced in my bone marrow. B cells are the component of our immune system that responds to invaders (like viruses) and creates antibodies that protect us. Unfortunately, some of my B cells went rogue and started creating antibodies that attack my healthy tissue instead of a true invader.

Science has not been able to identify a specific trigger, but viruses, medications, environmental toxins, and vaccines are all possibilities. I’ve thought back to when my symptoms started, and I can’t think of anything that was different in Spring 2023. I hadn’t had a vaccine in six months. I hadn’t been sick. I didn’t take any new medications or use any strange chemicals. It’s really a mystery, and I will likely never know my trigger.

So, What Now?

The bad news is that there is no cure for pemphigus. It’s something I will have to live with for the rest of my life. The good news is that there is a handful of scientists and doctors who have made HUGE strides in treating this illness.

Until the advent of modern corticosteroids and immune suppressants, the disease was 95% fatal in less than 5 years. It’s still fatal for somewhere between 5-15% of patients – either from the disease itself or from side-effects of treatments. But most patients live a normal life span and are able to reach remission, some permanently and some temporarily.

In 2018, the FDA approved a drug for pemphigus – rituximab. There are other off-label treatments, but rituximab is considered the most effective – bringing roughly 88% of patients to remission. Sometimes the treatment just takes two rounds, sometimes it takes 5 years of treatment with complementary IVIG and prednisone therapy. Every patient is different.

Rituximab was FDA approved in 1997 to treat the blood cancers lymphoma and leukemia. Like pemphigus, both of those cancers involve B cells gone bad. Since the drug came onto the market, it’s been found to also be effective in treating a whole list of other B Cell mediated autoimmune diseases.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that is administered by infusion, like chemotherapy. Monoclonal antibodies are lab-created proteins that mimic the function of antibodies. Rituximab, specifically, is a B Cell depleting therapy. Once it is infused into my bloodstream, it will attach to all the B cells in my immune system – both good and bad – and destroy them all. Within just 72 hours of my first infusion, I will be fully depleted of B cells.

For about six months after treatment, my body will have no B Cells. I will have no ability to produce new antibodies or fight new infections. I will be very fragile for a time, but the hope is that when my immune system slowly ‘reboots’, it will come back online without the rogue B Cells that are causing my skin to fall apart.

I’ll start with two rounds of treatment, followed by bloodwork 6-8 weeks after the second round. My auto-antibody levels in that bloodwork will be used to determine whether or not I need more rounds of treatment.

I still have a few more weeks to wait for my first infusion. I’m so eager to get started and I’m feeling hopeful for the first time in a long while.